The guy who rose some controversy this past August by criticizing George Martin’s series, wrote possibly the very best review ever of Gardens of the Moon. It’s quite enlightening and wonderfully focuses on important aspects of that novel that are often dismissed or overlooked (including myself).

Some quotes:

You see, as with most sword and sorcery stories, and especially given its kitchen sink approach to fantasy tropes, there’s a danger that Gardens of the Moon won’t quite pass the giggle test, what with its floating mountain, assassins and thieves guilds, and hulking fantasy stereotype Anomander Rake. Erikson defuses this by starting off grim. By present standards, Gardens of the Moon is not a really dark book, but its darkest moments are at the beginning to set the tone.

From this bleak beginning, Erikson moderates the tone and eventually introduces various elements that, considered in isolation, would seem pretty silly. But these are defused by the inertia of that serious beginning and the constantly down-to-earth attitude of the main characters.

Erikson is actually pressed for time. In traditional fantasy, diverse groups of characters band together to achieve some sort of goal. In Gardens of the Moon, everyone has their own thing going on, resulting in not just one plot, but over a dozen. Only strong unities of place and time keep the novel from feeling more like a short story collection.

Again turning to Lord of the Rings as a useful model, the timespan of that story caught almost every important event. Aragorn had been alive for over a hundred years when he meets Frodo, but little of what he was doing had much impact on the outcome of the story. The same is true for most of the other characters. Ask a character after the events of Lord of the Rings when the important time of their lives was and all would point to the War of the Ring. Gardens of the Moon is completely different. The older characters (and even some of the younger ones) have been active for years and this is just the latest situation they’ve had to confront.

Tolkien probably felt our world was about 6,000 years old and so was his Middle Earth. Erikson no doubt sees our world as much older, and this is likewise reflected in his fiction. The Malazan Empire is just the latest of a thousand civilizations, a tiny sliver of hundreds of thousands if not millions of years of history. And this being a fantasy, there are immortal characters who have seen a sizable fraction of that history. Unlike Tolkien, who maintained a generational distance from the events of myth (Elrond was present only for the events at the very end of the Silmarillion), the influential immortals of Erikson’s present were just as influential in past millennia. This results in a unique effect where the past can feel extremely distant in one scene and very immediate in the next, depending on who is present.

Now, having made such an extended comparison to Tolkien, I have to make clear that although Erikson’s world has a depth similar to Tolkien’s, he is a very different writer. He doesn’t share Tolkien’s gift for languages, nor does he lavish nearly so much attention on the landscapes. Erikson was a professional anthropologist, so the details he emphasizes are those of culture. When Tolkien described a hill topped with ruins, he spent most of his time on the hill, whereas Erikson lingers on the ruins. The result is that Erikson’s landscapes are not beautifully evoked, but they come off as being genuinely inhabited (whether now or in the past) in a way that Tolkien’s empty countryside does not.

Whereas Tolkien’s world was fundamentally Christian, Erikson’s is thoroughly pagan. His gods are capricious and quick to interfere in the affairs of mortals. There’s no sense that humanity has dominion over the earth…the opposite, in fact.

That disparity in power is perhaps the most old-fashioned element here. It’s easy to forget that for all the inequalities of wealth in our era, most people deny there is much difference between the average person and, for example, the American president. But to the ancients, there was an enormous gulf between the lowly peasant and Pharaoh, son of Ra.

However, mixed into this authentically ancient outlook is a very modern flavor. Unlike traditional Tolkien-influenced fantasy, the past is not considered better, nor is the present a slide down into a faded future. Oh, there were still powerful races and empires in previous eras who forged mighty artifacts and fought incredible battles, but while they are certainly due some respect, ultimately there is an assumption that modern magic is just as good as the old stuff, if not better. Even the Jaghut Tyrant, an ancient evil feared by all and the closest thing in the novel to a Dark Lord, is implied to be somewhat obsolete and rather out of his depth.

Even the Bridgeburners, who are indeed glorified as a legendary military unit and present some of the most interesting and sympathetic characters, turn out to be ambiguous at best, given they attempt to orchestrate murders and then prepare a terror attack on a civilian population. They are well-intentioned, but so are their enemies who live in Darujhistan. When they meet in the right circumstances, people from the two different sides even become fast friends. Yet the intentions of ordinary people cannot change their world, so the conflict continues, grinding up human lives in the vast gears of ambition and intrigue.

It’s Erikson’s achievement (and this is, in my opinion, a considerable achievement) that not only do we as readers immediately have the same reaction as Crokus but we have it for the same reason. Immersed in the Malazan world with its manifold deities and deep magic, there’s nothing implausible about the idea of beautiful gardens under an ocean on the moon tended by an elder god. No, the only thing that seems unbelievable about Apsalar’s description is its last image: “There won’t be any more wars, and empires, and no swords and shields.” An end to suffering and war? That’s just fantasy.

The pain with this book more than reading it is trying to write a review. How to frame it? It left me reeling for sure. There are a number of ideas explored that seemed to echo with some my own thoughts pre-existing the book, this further reflected toward the end of the book by a strong in and out of text deja-vu whose implications are far too tangled for me to make any sense of them (I should also try to second-guess some that Bakker did, that would bring a whole new level of complication). Just to say: the book messed a bit with my head. But that was almost expected, knowing well the kind of writer. The blending in and out of character, in and out of the book, and between facets of different characters echoing each other is a prevalent defining trait.

The pain with this book more than reading it is trying to write a review. How to frame it? It left me reeling for sure. There are a number of ideas explored that seemed to echo with some my own thoughts pre-existing the book, this further reflected toward the end of the book by a strong in and out of text deja-vu whose implications are far too tangled for me to make any sense of them (I should also try to second-guess some that Bakker did, that would bring a whole new level of complication). Just to say: the book messed a bit with my head. But that was almost expected, knowing well the kind of writer. The blending in and out of character, in and out of the book, and between facets of different characters echoing each other is a prevalent defining trait. Pat received the

Pat received the

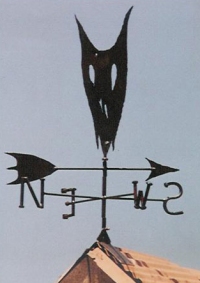

“Mock’s Vane” is the object whose description opens the Prologue of Gardens of the Moon. I was briefly discussing its description on Westeros forums when I noticed that on Tor reread it was interpreted in a completely different way, without triggering any debate. So I thought it was worth elaborating here.

“Mock’s Vane” is the object whose description opens the Prologue of Gardens of the Moon. I was briefly discussing its description on Westeros forums when I noticed that on Tor reread it was interpreted in a completely different way, without triggering any debate. So I thought it was worth elaborating here. It makes sense but I think my interpretation is more accurate and convincing. I’m not a particularly intuitive guy and these things usually defy me, but in this case I used a rather simple framework. I took the object and divided its basic qualities. Those traits will probably qualify what the vane stands for/symbolizes.

It makes sense but I think my interpretation is more accurate and convincing. I’m not a particularly intuitive guy and these things usually defy me, but in this case I used a rather simple framework. I took the object and divided its basic qualities. Those traits will probably qualify what the vane stands for/symbolizes.