This book, and series, is particular to begin with because it’s very rare to see discussed in the usual places. It could appear as some old series buried and forgotten, written by a writer that was well known at one point but didn’t quite make into the Big Names that continue to be relevant. Instead this is a series “in the making”, right now. Series’ name is “The Wars of Light and Shadow” and will be completed (it will) in 11 volumes. The 9th comes out in October of this year and usually one can look forward to a two-years gap between each volume. I tend to have quite a bit of trust in the writer as I’ve read in her forums and interviews that she never strayed from her original plan and is strongly against series that “sag or sprawl”, as well as cliffhangers at the end of the book. In fact this series is structured in five different arcs, with each giving closure to the story at hand (this is true for the first book, that makes a single arc on its own).

This book, and series, is particular to begin with because it’s very rare to see discussed in the usual places. It could appear as some old series buried and forgotten, written by a writer that was well known at one point but didn’t quite make into the Big Names that continue to be relevant. Instead this is a series “in the making”, right now. Series’ name is “The Wars of Light and Shadow” and will be completed (it will) in 11 volumes. The 9th comes out in October of this year and usually one can look forward to a two-years gap between each volume. I tend to have quite a bit of trust in the writer as I’ve read in her forums and interviews that she never strayed from her original plan and is strongly against series that “sag or sprawl”, as well as cliffhangers at the end of the book. In fact this series is structured in five different arcs, with each giving closure to the story at hand (this is true for the first book, that makes a single arc on its own).

It wasn’t in my reading queue as I had never heard about the writer, but curiosity took over. I certainly like Grand Plans in literature, akin legendary human achievements, and the more I started to gather information the more curious I got. Especially because of what I read in a interview, about the approach to the writing and the series. The name already gives a good idea about the central conflict that builds it. A war of “light” and “shadow”, mirrored by two brothers, opposite in nature and natural magic proficiency. The 800 pages of this first book are quite focused, the two main characters are the two brothers and the PoV rarely drifts away from them. The setting is broad and sprawling (at the periphery, since only a small chunk of the landmass shown in the map is actually explored) but there are only a dozen or so characters that gravitate around the two brothers. So the story is rather railed on its way and doesn’t sprawl. After 200 pages or so the course is set and one has the idea of the type of story that is shaping up. More confusing at the beginning, there’s a short opening page written from a point “out of time” (relatively, meaning an epoch distant from the one where events take place) that already frames this primary conflict, filling it with foreboding.

The story then opens not in some isolated farm or village at the periphery of the map, but outside the map itself (with me wasting a lot of time to find the location in the almost illegible map in the minute paperback, location that obviously wasn’t there). Another world, in fact, linked by portal. Only after the first 100 pages the two brothers get exiled and actually enter the “world” where the rest of the story will take place. Here the two brothers are immediately “rescued” by the “Fellowship”, a group of seven wizards that waited for this arrival for a long time, and that have already woven them tightly into their own plans (the “free will” is an important theme here). Athera, the world they come to, is plagued by some sort of curse in the form of a mist that completely obscures the sky, keeping this world in a permanent gloom, without sun or starry skies. The premise appeared to me quite ridiculous and fancy, but this superficial level is not the deal, and there’s indeed an interesting world hidden below (the mist).

Lead by prophecies, the first task that the Fellowship appoints to the two brothers/mages/future kings is to join forces, and powers of “light” and “shadow”, against this unnatural mist, so that Athera will be able to see a clear sky again. But this also becomes the trigger for the main conflict and the origin of all woes. The Fellowship’s plans and reasons are given a full exposure. They aren’t treated like an hidden manipulative organization with shady purposes. You can see the conflict of their motivations, of cause and effect. Be there when they decide the next move. Through a sort of “mage sight” they can “scry” all possible future events, and then decide which course to take. But the Mistwraith, the mist that covers the world and that arrived through another of the world portals, is an element “outside” the picture that doesn’t follow their know rules, and so can easily avoid prediction and distort the outcomes.

That element, and quite pivotal being the seed that sparks the whole conflict, is the part I liked the least. The first part of the novel is a very good description of the conflicted relationship between the two brothers. It opens amidst war and Arithon (the “shadow” brother) is taken prisoner. From this point onward the two brothers face each other directly, and slowly come to understand each other. The conflict is eased, almost resolved. But this is only the early part of the book and one is already well aware that the rest of the series is founded on this particular conflict. That’s the problem. This precise and deep, solid characterization is taken over by an escamotage. Essentially the whole conflict is sparked again by magic possession. It’s not truly convincing and it disrupts the work on characterization that precedes it. There’s some justification of what happens that surely grounds it better, but never coming off as so convincing:

Where opening did not already exist, the creature could not have gained foothold.

…But it certainly gives the decisive shove. The fantastic element becomes strength and weakness. The weakness I already described (the conflict has its root in magic, and magical unbalance) but it is also a strength in the way Janny Wurts builds this setting. The fantastic element is always a delicate part in fantasy novels regardless of who writes them. For many readers who prefer to stay away from the genre, the “fantasy” is something that opens a wide gap and so feels not relevant. Something alien or too estranged from a reality that is actual and matters. So a way to mystify truths, an excess of decoration. A fancy dress for a trite, juvenile argument. But here also lies the difference between the greatest fantasy writers and the rest: they use the “fantasy” not to dress but to strip reality of its layers. To reveal instead of hide. To go at the root of things, to understand deeply and without hypocrisy. As Janny Wurts said:

Fantasy allows discussion of sensitive topics with the gloves off.

That’s also the aspect I tend to criticize in the work of much bigger names in Fantasy. Martin being an example, being somewhat wary or suspicious about the “fantasy” element, and so keeping it almost off the page, far at the periphery, because it would upset the natural balance of a novel. And then without really understanding it and without knowing how it can be used once the series moves in that direction (a brilliant review of ADWD deals with these aspects).

This romantic idea of a world covered in mist, the plausibility of it and acceptance of the reader, are then the purpose of fantasy. Not to embellish or narrate of worlds that do not exist. But to speak intimately about ourselves. The inner world. The fantastic element is not a decoration or a veil that hides, but the coming of the revelation, a veil that comes off to let one see. It deepens the perception. And that’s why fantasy has the responsibility to stay grounded and cling to something that has to be meaningful and necessary. Not consolatory wishful-thinking, but language that is powerful and ambitious in its purpose.

I put Janny Wurts in the wide area of Erikson or Bakker for these reasons. Writing the “pretentious”, ambitious fantasy. Writing in the genre as a strength instead of a liability. With a clear vision of what they are doing and why. Janny Wurts has a far more classical/romantic style that keeps her more apart, even if not shying away from the brutality of the fight that closes the book. She keeps all the sharp, “gritty” edges, not blunted by romantic undertones (that are still there aplenty). The book has the vague feel of the Wheel of Time, but written from an adult and “serious” perspective. It has the strong classical feel and embraces the fantasy element, but the setting is solid and realistic, perfectly nailed and one of the best described in the genre. So is the magic, I’ve never seen (or thought possible) to describe magic in a so vivid way. It’s tangible. Whereas magic is usually kept vague and abstract, only dabbed in description, Janny Wurts describes minutely the details and behaviors, managing to make sense of it and keep it consistent. Often compared to the complexity of music and its rules, that can then be analyzed through great effort and manipulated:

a loophole in the world’s knit that hinged on a theoretical blend of fine points

The Fellowship, the group of powerful wizards that take care of the world, is not kept distant from the reader. The book offers their PoV directly and so the description and interpretation of their use of magic. They even behave as you’d expect of people wielding that kind of power and awareness: by manipulating directly every event in a brutal, arrogant way, yet coming off as the “good” guys. Even if in the end their actions become self-serving, and their attempts to restore their own power triggers all sort of cascading disasters. Relatively “good”, as this is another series that pivots around the idea of “gray” characters only driven and justified by their motivations. In the same vein of “modern” fantasy that “doubles” and opposes the PoV, treating equally both sides caught in a war. In this book this is the real driving theme, as the conflict between “light” and “shadow” is driven by respective flaws. It’s a story about making hard choices, accepting compromises that imply costs impossible to tolerate, and yet taking responsibility for all of this.

Whose cause took priority? In this world of divisive cultures and shattered loyalties, no single foundation of rightness existed.

But beside all this, it’s really a weird book and not one that I can easily recommend. The prose is an aspect I left on the sideline but that is the most important when it comes to decide whether or not to read this book. It is so lush and thick that it’s almost impossible to extricate (feels like work). I can’t even imagine how it can appear to those who use to “skim read”. It requires a lot of attention to keep track of things and there’s the constant risk that the eye glazes over, so you always have to keep that control and not sink whole in the prose. Beautiful, beautiful prose, surely, lush descriptions and minute, chiseled characterization and psychology, but it requires an effort.

Amid that graveyard of ravaged splendour, of artistry spoiled by war in a cataclysmic expression of hatred, arose four single towers, each as different from the other as sculpture by separate masters. They speared upward through the mist, tall, straight, perfect. The incongruity of their wholeness against the surrounding wreckage was a dichotomy fit to maim the soul: for their lines were harmony distilled into form, and strength beyond reach of time’s attrition.

A prose that soars, but in a way that often risks to become a huge yawn. The reader is only human, and attention has always the tendency to slip off. Not all that much brisk dialogue that feels like a chilly breeze. You often have to wade through beautiful, but thick, paragraphs of intricate description (of both psychology and landscape, treated equally). And yes, the book is SLOW. There’s a point where I draw the line, though. I don’t feel that the book meanders or overindulges in description of stuff that is not relevant. This prose is not opaque or rhetoric or redundant. Under there there’s some impressive characterization and masterful control of storytelling. As I said: it’s not a fun, brisk pageturner and it demands and clear, focused mind, but the purple prose is not superficial decoration and has always the root into something meaningful. Which is why, despite the effort, I also kept the determination.

Oh, and the fanciest of sex scenes:

In the sunwarmed air of their sleeping nook, he allowed her quiet touch and hot flesh to absorb his bitter brew of sorrow.

Another potentially problematic aspect is that despite a neutral approach to the characters, it’s Arithon to lead the way. He’s the one who retains a certain awareness, and the one that is most sympathetic. But he’s also the one with a supernatural sensibility and comes off as the “emo” type. Maudlin, always contemplative, with a Christ-like spirit of sacrifice (that brings its own flaws). You share with him all his thoughts, psychology and development, and this also takes its toll if you don’t like to indulge in this kind of analysis. On the other side Janny Wurts writes this kind of character splendidly and never falls into a boring or redundant cliche. It brings back to the essence of the writer, that is: to care. The quality of being born many times, and so become different characters. Be in their place. To feel. So this book demands a similar care and patience.

This makes a kind of slow, contemplative writing that is not for everyone. What I’m saying is that this “mist” or noise is still well rooted into something meaningful that made the effort worthwhile in my case. I’m looking forward to see the story open up and expand, less constricted by a relatively formulaic first book that is only the spark that sets the fire. From the first pages of book two (that opens the second cycle) it seems that there’s a gap of at least five years, so the story will surely grow from its premises and I’m curious about where it will go since the writer has said that every step has a point in the Grand Scheme of Things, and everything will converge for the closure of the series.

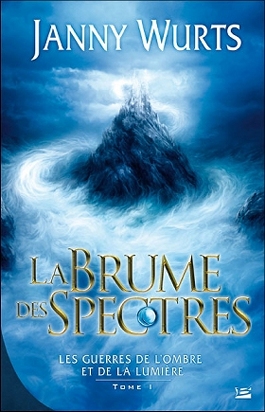

Bonus, the french covers. That are both beautiful and pertinent to the content of the books:

This book, and series, is particular to begin with because it’s very rare to see discussed in the usual places. It could appear as some old series buried and forgotten, written by a writer that was well known at one point but didn’t quite make into the Big Names that continue to be relevant. Instead this is a series “in the making”, right now. Series’ name is “The Wars of Light and Shadow” and will be completed (it will) in 11 volumes. The 9th comes out in October of this year and usually one can look forward to a two-years gap between each volume. I tend to have quite a bit of trust in the writer as I’ve read in her forums and interviews that she never strayed from her original plan and is strongly against series that “sag or sprawl”, as well as cliffhangers at the end of the book. In fact this series is structured in five different arcs, with each giving closure to the story at hand (this is true for the first book, that makes a single arc on its own).

This book, and series, is particular to begin with because it’s very rare to see discussed in the usual places. It could appear as some old series buried and forgotten, written by a writer that was well known at one point but didn’t quite make into the Big Names that continue to be relevant. Instead this is a series “in the making”, right now. Series’ name is “The Wars of Light and Shadow” and will be completed (it will) in 11 volumes. The 9th comes out in October of this year and usually one can look forward to a two-years gap between each volume. I tend to have quite a bit of trust in the writer as I’ve read in her forums and interviews that she never strayed from her original plan and is strongly against series that “sag or sprawl”, as well as cliffhangers at the end of the book. In fact this series is structured in five different arcs, with each giving closure to the story at hand (this is true for the first book, that makes a single arc on its own).

To escape his country’s harsh economic conditions, Jeon Seung-chul (played by the director) defects from Musan, North Korea to Seoul. He ends up living in the city’s rundown outskirts and makes ends meet putting up street ads. His only satisfaction is going to church, where he meets and becomes attracted to Sook-young, a choir singer who works in a karaoke bar by night. The Journals of Musan depicts the tremendous difficulties North Koreans have integrating in the capitalist society of South Korea, where they are often marginalized and subjected to discrimination.

To escape his country’s harsh economic conditions, Jeon Seung-chul (played by the director) defects from Musan, North Korea to Seoul. He ends up living in the city’s rundown outskirts and makes ends meet putting up street ads. His only satisfaction is going to church, where he meets and becomes attracted to Sook-young, a choir singer who works in a karaoke bar by night. The Journals of Musan depicts the tremendous difficulties North Koreans have integrating in the capitalist society of South Korea, where they are often marginalized and subjected to discrimination.