|

The events that accompany the release of one of Erikson’s books are the release of the prologue followed by the cover art, then the hunt for the first comments and reviews. The book itself should be shipping around the beginning of September if delays don’t happen.

Today is the day of the first two events, since the mass market release of the previous book (Toll the Hounds) is already being shipped to selected few. Here’s the prologue and the cover.

As always, this was followed by my usual rant about the cover (bring me Komarck or Swanland, this “guy on a horse with both guy and horse smiling at the camera under sunset” is as generic and unsubstantial as it could be). But then another event promptly reminded me that things could be worse. MUCH worse: EDIT: Beside the diplomacy, Sanderson doesn’t sound too happy either. |

Tag Archives: Books

Three different kinds of epics

Romance of the Three Kingdoms – Luo Guanzhong – 2000/3000 pages approx.

One of the “Four Great Classical Novels” of Chinese literature. It’s a huge book but as for every chinese classic it’s quite hard to figure out the best version to get. All books available in english seem to be abridged in a way or another, and also quite expensive. On Amazon I tracked two fine-looking versions. The first (C. H. Brewitt-Taylor) is the one in the picture above and easier to get from various places. Two volumes of 600-700 pages each. The other version (Moss Roberts) is divided into four volumes, declared unabridged and more faithful to the original, while the first seems to have a more beautiful prose. You can compare the two directly since Amazon has the “look inside” option for both (but the latter is taken from the abridged version). My choice would be on the four volumes version, also because even the abridged version seems more easy to follow and less obscure. (an unabridged version is also available for Kindle)

Comments from wiki or reviews:

A grand total of 800,000 words, nearly a thousand characters, and 120 chapters.

Myths from the Three Kingdoms era existed as oral traditions before any written compilations. In these popular stories, the characters typically took on exaggerated characteristics, often becoming immortals or supernatural beings with magical powers.

how power is wielded, how diplomacy is conducted, and how wars are planned and fought.

Three Kingdoms takes place amid a time of disorder in the Chinese Empire caused by the weakening of the throne and the Yellow Scarves rebellion. It focuses on the interactions betweent the various warlords. The Yellow Scarves who are losing influence at the time are mostly a background “random events” threat that serves the function that the Reivers do in Serenity.

Three Kingdoms is curious among the epics I am familiar with because of the emphasis on cunning. Reading it is very much like watching a chess game being played out and the book is full of that style of mysticism of strategy that seems unique to China. In fact that is why I got it; I was seeking just that sort of thing.

For that reason it will be different from more familiar epics. It has labyrinthine cloak and dagger, and treachery, described in a strange style. It is one of the most elaborate tales of intrigue ever written.

Jin Ping Mei – Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng – 3000 pages approx.

Or Chin P’ing Mei. This is the fifth of the four great chinese novels:

It is the first full-length Chinese fictional work to depict sexuality in a graphically explicit manner

The novel describes, in great detail, the downfall of the Ximen household during the years 1111-1127 (during the Northern Song Dynasty). The story centres around Ximen Qing 西門慶, a corrupt social climber and lustful merchant who is wealthy enough to marry a consort of wives and concubines.

Reputed to be the most extensive and notorious work of pornography in world literature, the Chin P’ing Mei is actually far more than that: with its grasp of human psychology and mastery of complex narrative forms, its author probably created the world’s first realist novel.

Now this is even harder to find in an unabridged version. I actually had an italian copy I bought years ago and tried to compare with a few versions online: it doesn’t even seem the same book. It’s not a matter of translation, but totally different story and characters. This version I have is about 900 pages and is even “extended” over the first, ad I think based on the translation of Arthur Waley whose other book/translation (The Tale of Genji) was considered beautiful in style but also lacking faithfulness to the original and even missing one chapter. There’s only one version (The Plum in the Golden Vase) in english that is completely unabridged and faithful, the only big problem is that the professor who was working on this project planned five volumes (600+ pages each) but was only able to finish three before his death. So the only decent translation available in the western world is incomplete.

From what I remember of my italian version it was quite a fun read because of the characters and libertine, unrestrained behaviors. Easily readable and compelling. The few sexual scenes were also tamer than anyone would expect, at least in that version. There wasn’t anything really “explicit” and when things were described they were only done through allusions and fancy, poetic metaphors with flowers, fishes and springs. I’d really like to buy the english version and compare it with the one I have, but the three volumes aren’t exactly cheap and the incompleteness just adds to the disappointment. This would be a great story to read.

Arcana Coelestia – Emanuel Swedenborg – 4000 pages approx.

Many years ago I was reading all sort of weird stuff. But really weird and all over the place. From magic, to myths, literature. Esotericism mixed with science, like The Morning of the Magicians. Not that I believed in that stuff, but I’ve always been curious. Along the path I started to read the Inferno by August Strindberg. That was one of the best books I’ve ever read. Like a victorian/gothic tale written by E.A. Poe or Lovercraft, but a real story in this case. An autobiography/diary of a writer gone mad, paranoid, hallucinated, obsessed with coincidences, occultism and alchemy. It’s one of those books you can’t stop reading once you start, written splendidly and fascinating (besides, there was an implicit intrigues between Strindberg himself, his lover, one friend and Edvard Munch, a fine group). In this book Strindberg wrote how the Arcana Coelestia by Swedenborg changed his life and gave an explanation to all his obsessions. Swedenborg also had strong influences on Goethe, Balzac, William Blake, Baudelaire, Borges, Kant, Martin Luther King and, in particular, Carl Jung. So I went and tried to order the book, and continued trying for a couple of years. Now I understand why I was never able to find a version. The published book is more that 4000 pages, the only printed edition I was able to find is divided into 12 volumes. But it is also available for free online.

There are a lot of resources online about Swedenborg, but they look rather close to stuff like scientology. The Arcana Coelestia is a monumental book where he explain the first book of the old testament, the Genesis. He says that it shouldn’t be read in its literal sense, but in its symbolic sense. That’s why Jung was influenced by his works. Modern psychology has moved through five stages that I don’t remember exactly. But it moved from the basic sense of a dream, to Freudian interpretation, to a deeper symbolic one (Jung) and then an even deeper level (Hillman, whose “The Dream and the Underworld” I heartily recommend) called archetypal psychology where dreams go back to the archetypes coming right from Greek mythology. The deeper you dig, the farther you go. There are similarities with Swedenborg as he interprets the bible like Hillman would interpret a dream. Swedenborg also claimed that he was able to talk directly with god and various angles for many years and that all he wrote was exactly what was being told to him. Something like Dante’s Divine Comedy, but pretending it wasn’t in any way fictional. He also wrote a book where he explains the apocalypse (1200 pages, enjoy), again in its symbolic meaning and purpose.

Whether you believe, or even doubt, about the relevance of all this, at least it is intriguing and may have a deeper sense if read from the point of view of Hillman and Jung (so through critical thinking and not taken as dogma).

Swedenborg shows that the Bible has a external or natural sense (the stories) and an internal or spiritual sense (the inner meaning). The spiritual sense of the Books of Genesis and Exodus teaches of the development of the human mind and the regeneration of humans.

The truly astounding thing to me about the Arcana Coelestia is that it tells about the life of Christ–His inner temptations and growth–things we don’t learn about in the Bible. So while it gives new light to the Old Testament, it also adds to the New Testament and knowledge about Christ.

I spent years researching the five major religions and have read all of their main sacred texts, yet I never seemed to find clear answers to my questions or an explanation to the frustrating contradictions between common religious beliefs. Heaven and Hell put all that frustration to rest. This magnificent work presents a coherent theological model in which all major religions find a place and answers all questions people typically have about faith such as: why religions sometimes contradict; why people in various cultures developed a belief in reincarnation; the cause of gender and sexual love; what the concept of “eternity” truly means; why evil is permitted in this realm and so on. Swedenborg was the most powerful psychic in known history, someone whose work cannot be ignored by any serious student of religion or philosophy.

Swedenborg wrote over 30 volumes of work, so figuring out where to dive into this ocean of material can be confusing. “Heaven and Hell” is a great place to start. Have you ever wondered about what Heaven looks like or what goes on there? If you have ever been curious about Angels and what they spend their time doing, you will have all these questions and more answered in this detailed account. Did God create hell so there would be a place to send sinners to be punished? Swedenborg says, “No.” God does not punish or judge anyone. God is pure love and incapable of even frowning in our direction. Want to know who created hell and who goes there? You have to buy the book….

These recent English translations are a very interesting read for the “open minded”. Swedenborg’s matter-of-factly presentations of what he says he saw and heard is expressed so honestly, the reader is left with much to ponder on many “other worldly” topics. The author appears to truly believe the experiences he relates, and passes descriptions along to us in vivid detail, almost to a fault.

Books at my door – Late March

I really need a camera so I could post porn pictures of books. Anyway:

The Judging Eye – R. Scott Bakker – 420 pages

I diligently bought all the books part of this series even if I’ve yet to read one (a matter of time ans subjective reading pile order). This one is the first volume of the second trilogy set twenty or so years after the previous. Usually Martin’s fans prefer Bakker to Erikson and all three together can be considered the apex of epic fantasy today. This book was well received from the first reviews on the internet, but I also read more moderate, less enthusiastic opinions. Surely Bakker aimed high, as he said a while ago that his first trilogy would be like “The Hobbit”, while this one following would be his “Lord of the Rings”. Those reviews say that the book is interesting and well written as always, but it also reads like an introduction to what may come later, so it looks like even this year Abercrombie is going to steal the spotlight.

That cover is from the Canadian paperback edition, the one I got. This as a protest to the American publisher (Overlook). This book had one of the coolest covers ever made. I was anxious to buy the book just because of the sexiness of it. I already commented that I love books with covers that makes them look like books and not like b-movies billboards. This one was perfect but about two months before release the publisher decided that it was TOO cool, and switched it with the UK version with some slight changes. So I stubbornly went to amazon.ca and bought a different version. The book ends with a few pages of glossary, some more pages of summary about the previous trilogy, and an updated map reasonably printed, this time.

NOTE: Even the cover you see there is not correct. The book I received has a slightly different cover, more elegant. The horns appear more ornate and inscribed, the tone of the colors is more toward light brown than yellow, and at the very bottom there’s a vague representation of a landscape.

Reality Dysfunction – Peter F. Hamilton – 1225 pages

Oh, I love these fatty books. Mass market UK edition, also first in a trilogy, but a trilogy that ended and that didn’t originate sequels. The format here was a constant. All three books have the same number of pages. 400k words for a total of 1M 200k. Reading comments around it seems that this series is, along with the Gap by Donaldson, the very best among the space operas (then comes Banks). Something like epic fantasy in space, with huge cast of characters, proliferation of plot lines and usual big scale conflict. It was also described as a true page-turner. So I expect to have fun reading without the fear the fun being over too soon. This book not only part of the series considered by far his (author) best, but also the best volume in the trilogy. The other two seem slightly more predictable and less involving, even if they continue to play well the same cards that worked in this first one, and play them well. Or so they say.

I always said that I’m not interested in the “science” part of science-fiction (hard SF), in this case Hamilton is obviously favoring the spectacular side, but is also known because he crams a shitload of geeky ideas in his books, so working toward consistence. But I really want a true page-turner. That’s the main reason behind the purchase.

Bleak House – Charles Dickens – 1040 pages

Great Expectations – Charles Dickens – 510 pages

I never read Dickens, so along with the purchase of Drood came the curiosity. I didn’t know what to pick, so I gave a glance at the various books he wrote and picked these two. Dunno if it was a decent choice, but I expected to find something popular and relatively easy to read, instead it was the opposite. The writing here is incredibly dense and not easy at all to read for me (second language and all). The style is more like D F Wallace. Long phrases with plenty of commas and tangents within. It’s easy to get lost and have to go back at the beginning of the phrase to put everything together properly. Even quite ornate, with plenty of carefully picked adjectives everywhere. The writing is absolutely beautiful and researched. Deep, insightful, perfect. But it’s definitely not something “fun” to read. It’s like work. Great work, but still work. So I’m not expecting anymore to enjoy this. This about Bleak House. I don’t know if it’s just that book, Great Expectations seems to flow better and it’s also a leaner book. There are also plenty of notes in the middle of the text, so I read and then have to flip over to the appendices, it’s not fun at all. But then I’m stubborn and will try to go further.

You can understand my choices, though:

Like most Dickens novels, Bleak House is a wonderfully overpopulated work, crammed to the seams with grotesques, eccentrics, amiable idiots and moral monstrosities.

On the surface at least Bleak House is a ramshackle, dishevelled book, a centrifugal novel that spins off a whole galaxy of hermetic social worlds.

It is held to be one of Dickens’s finest and most complete novels, containing one of the most vast, complex and engaging arrays of minor characters and sub-plots in his entire canon.

Great Expectations is the most understated work by a writer not usually known for understatement: ”compactly perfect’, Shaw called it and its virtues from its compactness.

It is regarded as one of his greatest and most sophisticated novels, and is one of his most enduringly popular

Btw, Bleak House has illustrations, and Great Expectations a map ;)

Next time I’ll get David Copperfield.

Erikson’s ninth book almost finished

The last publication date I had read about Dust of Dreams was the beginning of September.

Calculating things and comparing dates to previous occasions it was about the time we received the prologue for the book, followed by its cover.

Latest news are slightly different, but still quite good: Erikson is later then usual finishing this book. The reason seems partly about some “massive battle scenes” that conclude the book and that are taking more time than usual. The book is still scheduled for the same date but it may get delayed (still within the year almost for sure).

Hetan on Malazan forums was more precise and said that currently Erikson is working on the last two chapters of the book (by Erikson’s standard about 90 pages on a total of 900). We’re close, and the book requiring more work is a good thing, even if “massive battle scenes” don’t work as a solid argument for me. I prefer strong, meaningful plot with the right revelations and things falling smoothly in their right place. Diversions! Deceits! Reversals! Upheavals! The exhibition of cool things is nice, but a coat of shiny paint over what’s meaningful.

I already commented that I find him less incisive when he tries too much to impress. I expect from Erikson so much more than pretty fireworks.

I want sleight of hand.

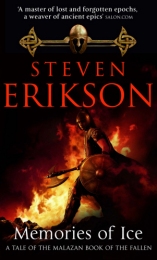

Wizard’s First Rule – Terry Goodkind

My reading pile is so high and filled with awesome that one wonders why I waste time reading Goodkind, especially considering I’m a slow (but steady) reader that has yet a vast ground to cover before feeling satiated about what the genre has to offer. The reason is simply curiosity. Some writers are loved everywhere, some writers are niche, some bring controversy. In the blogs and forums I read Goodkind isn’t just considered an example of the worst, but also a receptacle of laughter and continuous mocking. The books as its fans. I read this book in parallel with Memories of Ice and The Colour in the Steel of KJ Parker. Quite different stuff in style and intent, meant to be, so that I could gleam better what makes all these writers different. Since I re-started reading fantasy and sci-fi, about a year and half ago, I tried to pick representative writers and books, vastly different one from the other. I do a lot of “research” (meaning reading plenty of reviews online and forum threads) before buying a book and, no matter what I plan, at the end I start reading the one that makes me more curious. In this case it felt a perfect companion (like their opposite) to the books I was reading, and I was curious to know how bad it was to deserve all that negative noise, and yet why it was also hugely successful with the larger public. The goal was to find a convincing answer to both questions.

My reading pile is so high and filled with awesome that one wonders why I waste time reading Goodkind, especially considering I’m a slow (but steady) reader that has yet a vast ground to cover before feeling satiated about what the genre has to offer. The reason is simply curiosity. Some writers are loved everywhere, some writers are niche, some bring controversy. In the blogs and forums I read Goodkind isn’t just considered an example of the worst, but also a receptacle of laughter and continuous mocking. The books as its fans. I read this book in parallel with Memories of Ice and The Colour in the Steel of KJ Parker. Quite different stuff in style and intent, meant to be, so that I could gleam better what makes all these writers different. Since I re-started reading fantasy and sci-fi, about a year and half ago, I tried to pick representative writers and books, vastly different one from the other. I do a lot of “research” (meaning reading plenty of reviews online and forum threads) before buying a book and, no matter what I plan, at the end I start reading the one that makes me more curious. In this case it felt a perfect companion (like their opposite) to the books I was reading, and I was curious to know how bad it was to deserve all that negative noise, and yet why it was also hugely successful with the larger public. The goal was to find a convincing answer to both questions.

I wasn’t even sure if I really wanted to stick with it from the first to the last page, I just wanted a sample. The fact that I arrived to the end is already a sign that I didn’t find it so horrid. Quite a page turner in fact. I’m not saying that I couldn’t put it down, but I had an easy time with it, more than with other, better books, and found myself reading further than the point I had decided to reach for that day. This due to a well-planned structure. Every chapter serves a particular purpose in a way similar to Jordan’s style, and every one chapter ends in a way that makes you curious about what happens next. Well balanced in all its parts. There isn’t any high peak in quality or particularly boring point. Mostly even with the exception of the last 100 pages, where all tensions vanishes and the plot comes to an end in quite a ridiculous way. Those last 100 pages are quite dreadful.

The whole beginning of the book instead went rather well. In fact I was writing on the forums that I was having an easy time reading it and that I considered it a relatively well written “young adult” fantasy novel, with the inclusion of some gruesome scenes. Well, that was before reaching the part with the PoV of the dark side. At that point isn’t a matter of violence and gore that aren’t suitable for younger readers, but scenes intended to be excessive. The problem of this book is that it takes itself way, way too seriously. So while it was working quite well as an accessible, easygoing and pleasant fantasy novel, it felt as if Goodkind started to add explicit violence and nasty themes only so that the book would have been taken seriously. As if he was marking the point and make sure he was going to be considered “adult”. Wannabe adult, but quite childish in truth. Childish and perverted at the same time.

Later on this point of view changed because while the book indeed has contrasting elements, it all brings back to one unitary view that then corresponds to a simplification of Ayn Rand philosophy. He didn’t just make parallels with themes, but also tried to replicate the reason behind the writing. Ayn Rand doesn’t write realistic characters, she writes only conceptual representations. She uses characters as precise embodiments of a concept, using them to explain this concept. They are descriptions of an intent, didactic. Means for an idea she wants to pass on. In the same way Goodkind creates characters, including main ones, more like archetypes than multi-faceted, complex figures. Slightly less conventional and already seen, as the archetypes aren’t typical of fantasy, but Ayn Rand archetypes (“The Queen’s tax collectors came and took most of my crops, they barely left enough to feed my family”). Richard, the seeker, doesn’t just acquire special powers because he becomes the seeker, but he actually becomes the seeker because he is already one. He already is the natural manifestation of the archetype itself. So he is chosen for the role, as a consequence.

This is both the weakness and strength. It’s quite obvious: if you don’t like when a whole book is meant to shove down your throat some strong ideology, then you’ll come to hate this book, because there’s really nothing “natural” or spontaneously going. It’s all driven to “mean”, from the first to the last page. On the other hand it quite works because while Rand’s principle aren’t smoothly working when dealing with real life, here the setting is serviceable and partial enough to be consistent with its intent. Fiction gives you that power, you can filter what you want and make sure your ideas work flawlessly. The simplification of Rand that Goodkind makes here works quite well and drives the story in an intriguing way. I mean, I hope you aren’t one who starts arguing at a book, because there’s A LOT to argue, plenty of brow-rising parts, but overall it works and exposes well some central themes, like the manipulation of masses. Even the “Wizard’s First Rule” is well explained and meaningful in the book. Sometimes Ayn Rand works, in most cases when it corresponds to a simpler concept: pragmatism. The concept of “truth” simplified in the book often corresponds to pragmatism, or what is true bared of opinions. There are situations where people behave absurdly (like the mob of people going against Richard, Khalan and Zed at the beginning), but it’s still fun to read and find out how the various situations are resolved. Most of the book is built showing an impossible dead end, only to have the characters, Richard mostly, find a way out. Without too many tricks, in fact. Just a good use of the simplified principles and some slight deus ex machina to nudge things this way and that.

For most readers this layer of morals and philosophy will probably go above their head. It’s not even that central. Central is the narrow point of view on Kalan and Richard, their relationship. That’s the hook thrown at the readers. Even here the main protagonist is an handsome, yet naive boy who lives in a corner of the world without surprises. Quite a good and typical role for identification. The disclosure of the magical, mythical, foreign world happens through the eyes of this boy, so easier for the writer to gently introduce themes and details, because Richard knows just as much as the readers. Vehicle for experiencing and awe. Add an attractive, mysterious, even scary girl and you have already a recipe for win. At least a large public type of win. The PoV only rarely moves away from the central duo, so it’s quite “zoomed in” and intimate. Another strength is the heavy use of redundancy. This is not a book where you risk to miss details. If there’s something slightly important then be sure it is going to be repeated over and over, and then again. It’s already chewed food. But it works well in the style of a page turner, where your attention is on the characters and their adventures. That’s why I think in the end it works well and is quite fun to read, while on the other hand it juggles with some themes. There is the clash some people perceive and that may increase with the later books, where, I’m told, the preaching prevails on the adventure.

Later in this book there’s an endless part that deals with torture and imprisonment. At the beginning it felt like a reference to Jordan’s second book, where Egwene is captured near the end of the book, but in this case there’s an excess of violence that is marked over and over, and even a much stronger presence of SM themes. So much that it makes you wonder. Goodkind makes absolutely sure that all the devious practices are exclusive of the bad guys, so he can point and put the blame on them and their evilness, but you wonder if in truth he enjoys these perversions in the end. Considering the increasing presence of these elements in the other books, the suspect is legit.

The part also made me think to “The Real Story”, first book by Stephen Donaldson in the Gap series. In this case the rape scene and theme is used to warn readers. It’s definitely not a book for everyone. Compared to Goodkind’s heavy handing it’s almost lightweight, but it’s way more unsettling even if it’s dealt less bluntly. In this case too Goodkind’s approach is more juvenile. “I’m bad, but ultimately good”. Versus the rape in the Gap series: “I’m bad, but if you look better, just gray”. Perverse, miserable and mean as most human beings. Amoral, filled with greed. So I think it’s the realism that makes the Gap case unsettling, while it quite doesn’t work the same in Goodkind. The tale is spoiled. First because you know where it goes, you know there will be the happy end. Second because there’s no real “letting the plot loose”. Goodkind follows solid principles, he uses the book as a way to exemplify them, as a representative model. The moral is shoved down your throat because the book is an example of it. A mean for the end. The gap is more ruthless. You don’t really know where it is going, the characters are less predictable. The writer explores a character the way it is, not the way he ought to be. There’s a sense of uncertainty. In Goodkind it’s the opposite. You know how it ends, you are just waiting to discover what trick is being used to win, and by the end there’s even atonement, so everything is being forgiven and put under a positive light. Coming out clean.

In fact that part is so overdone that I started to make parallels not anymore with Jordan’s Egwene, but with Jesus. Richard goes trough a kind of experience that is not unlike “the passion”. Just in this case what drives him forth is not love for god (that would be quite a betrayal of Rand’s atheism), but love for his gal. So the love story goes on, raised to dramatic heights. Even though there’s plenty to dislike in this part, I read it, surprisingly, with interest. The way out of the situation was unclear and, despite the incessant repetition of the same situations, I continued to read and probably faster than the rest of the book. In fact once that part is passed the rest feels even anticlimactic and the tension goes suddenly down. But then you are at those 100 page before the end, so you go on.

Now my curiosity is mostly quenched by what I read and I doubt I’ll move soon to the second book. There’s a short excerpt at the end of the book that was interesting and different from the rest, so it’s still possible I continue even if I don’t plan to. Everyone out there says that the more the series goes on, the more the flaws stick out. Not exactly a deterrent as I can be more interested in controversy than adventure, the part that was quite successfully executed in this book. I know now how Goodkind exposed his side to attacks because of the weird and dubious mix of themes and the simplified, juvenile approach to them. At the same time I also understand why this series is so successful around the world. It’s accessible, has a good pacing and easy for identification. Then there’s Drama. And true love, heroism, friendship. Hell, there’s even an almost-sex scene surprisingly well written (the one at the Mud people, not the one later). Sex scenes are usually the low point in books, this one was the high one. Incredible.

I had a good time with the book. It worked perfectly as an interlude between the denser Erikson and KJ Parker.

Every book should be enjoyed for what it is and nothing more. This one isn’t THAT bad.

Wordcount of popular (and hefty) epics

Will now move HERE.

If you are curious, here some samples. The numbers are approximate and should omit indexes, appendices and stuff not directly belonging to the text itself.

Discrepancies are often due to the fact that Microsoft Word consider “it’s” like one word, instead my data is measured considering it as “it is”, so two words. This can usually add a plus 5-10k compared to Microsoft Word wordcount.

Lord of the Rings – J. R. R. Tolkien (revised to be in line with the rest)

The Fellowship of the Ring: 187k

The Two Towers: 155k

The Return of the King: 131k

Total: 473k

Wheel of Time – Robert Jordan

The Eye of the World: 305k

The Great Hunt: 267k

The Dragon Reborn: 251k

The Shadow Rising: 393k

The Fires of Heaven: 354k

Lord of Chaos: 389k

A Crown of Swords: 295k

The Path of Daggers: 226k

Winter’s Heart: 238k

Crossroads of Twilight: 271k

Knife of Dreams: 315k

Total: 3M 304k (official count)

Stormlight Archives – Brandon Sanderson

The Way of Kings: 387k (official count)

A Song of Ice And Fire – George R. R. Martin

A Game of Thrones: 298k

A Clash of kings: 326k

A Storm of Swords: 424k

A Feast for Crows: 300k

A Dance with Dragons: 422k

Total: 1M 770k

Malazan Book of the Fallen – Steven Erikson

Gardens of the Moon: 209k

Deadhouse Gates: 272k

Memories of Ice: 358k

House of Chains: 306k

Midnight Tides: 270k

The Bonehunters: 365k

Reaper’s Gale: 386k

Toll the Hounds: 392k

Dust of Dreams: 382k

The Crippled God: 385k

Total: 3M 325k

Forge of Darkness series/Trilogy:

Volume 1: 292k (very tentative)

Esslemont:

Night of Knives: 88k

Return of the Crimson Guard: 278k

Stonewielder: 237k

Prince of Nothing (and rest) – R. Scott Bakker

The Darkness that Comes Before: 175k

The Warrior-Prophet: 205k

The Thousandfold Thought: 139k

Total: 519k

The Judging Eye: 151k

The White-Luck Warrior: 200k~

A Land Fit for Heroes(?) – Richard Morgan

The Steel Remains: 146k

The Cool Commands: 171k

The Wars of Light and Shadow – Janny Wurts

Curse of the Mistwraith: 233k

Ships of Merior: 206k

Warhost of Vastmark: 156k

Fugitive Prince: 220k

Grand Conspiracy: 235k

Peril’s Gate: 300k

Traitor’s Knot: 220k

Stormed Fortress: 248k

Total: 1M 818k

The Night’s Dawn Trilogy – Peter F. Hamilton

The Reality Dysfunction: 385k

The Neutronium Alchemist: 393k

The Naked God: 469k (!)

Total: 1M 247k

Baroque+Crypto – Neal Stephenson

Cryptonomicon: 415k

Quicksilver: 390k

The Confusion: 348k

The System of the World: 387k

Total: 1M 540k

The Dark Tower – Stephen King

The Gunslinger: 55k

The Drawing of the Three: 128k

The Waste Lands: 178k

Wizard and Glass: 264k

Wolves of the Calla: 251k

Song of Susannah: 131k

The Dark Tower: 288k

Total: 1M 295k

Infinite Jest – David Foster Wallace

– 575k

Updated: 27 Oct 2011

Toll The Hounds in Mass Market

Transworld site updated today.

The Mass Market UK edition of Toll the Hounds is coming out the 9 April, meaning that it will likely be available on Amazon and retail a few days earlier.

Not only this is great news because I like to watch at a nice stack of 8 books all in the same format, but also because with this version should also come the prologue to “Dust of Dreams”, aka the beginning of the end.

The page count of this book is exactly like the previous, so 1280 pages.

Books at my door – Early March

Two from amazon.com to add to the reading pile:

![]()

Drood – Dan Simmons – 775 pages

I bought these two books from US Amazon because the UK editions aren’t as pretty. Usually it’s the opposite, UK has passable covers, while US has bad ones. In the case of this book the UK edition is passable, but the US one is just too good. And still not as good as the inaccessible limited edition. The one I have is the hefty hardcover. Quite a big book with rather thick pages. On the internet there are already plenty of reviews, the book came out less than a month ago so it’s “hot”. In general I read very positive comments. The story is like historical fiction. It’s about the last mysterious years of Charles Dickens and his obsession with someone named “Drood”. Story told from the point of view of his literate friend who actually existed and wrote at the time. Dan Simmons researched all this extensively so that it could be as plausible as possible, but at the end it’s a psychological horror/ thriller, made to grip the reader, and quite successful at that if you believe the reviews. Starting in typical fashion:

My name is Wilkie Collins, and my guess, since I plan to delay the publication of this document for at least a century and a quarter beyond the date of my demise, is that you do not recognize my name.

[…]

So this true story shall be about my friend (or at least about the man who was once my friend) Charles Dickens and about the Staplehurst accident that took away his peace of mind, his health, and, some might whisper, his sanity.

Viriconium – John M. Harrison – 462 pages

This was a suggestion to be intended somewhat like a challenge after I said on a forum that I liked Steven Erikson because of the way he experiments with the writing. This book is OLD, the bulk of it written 25 years ago. It’s a collection of shorter novels and novellas set around or about the same mythical weird city (Viriconium). Foreword filled with praises written by Neil Gaiman. It is known especially because it is supposed to have a very good prose and because it’s quite unconventional. In fact for a book this old and still so praised by everyone, it’s weird that it’s almost unknown to the largest public. I’ve read it as also an attempt to overthrow the way in Tolkien’s world everything is precisely determined and charted to the smallest detail. Viriconium is like a dream city, that changes and transforms, where character reappears by being someone else, and where plot makes more sense on a symbolic level than plain one. I only read 10-20 pages so I don’t know how much the book fulfills the premise, but it’s quite intriguing. The setting is about the “other kind” of fantasy. Instead of old medieval world we are here projected in the future after the fall of an advanced empire. Technology exists but considered alike magic as the new populations forgot how to make things and only know how to operate whatever is left. I guess the closer comparison is style and intent is Gene Wolfe. This edition of the book is very good, from the embossed cover to the irregular edge of the pages (exactly like the beautiful edition of the Fountainhead). One of those books I like to own as it may be another gem.

The next order is going to be slightly weirder than usual :) In the meantime I should try to review Godkind’s Wizard’s First Rule, since I’ve finished it a while ago, and already about 150 pages from the end of The Colour in the Steel. Still undecided about what to read next. I should go with Martin or Abercrombie, but I’m always more intrigued to read stuff from a completely (to me) new writer. So I start all these series and then leave them behind even if I loved them, while losing the timing and some of the enjoyment.

There’s also the fourth book of Steven Erikson that calls me. In about (or within) a month we should have the prologue of the beginning of the end (Dust of Dreams, as the prologue is usually included in the mass market edition of the previous volume, coming out in April). I can’t really read it to avoid spoilers, but I’ll chase all kind of feedback from other readers. Expectations are high.

Memories of Ice – Steven Erikson

Third book in the series. I started reading it with very high expectations. I knew from forums’ discussions and reviews that this third book was considered the highest peak in the whole series. I came from the previous two that I loved and, especially, after being AWED by the three novellas of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach. Those that won me over and got my unconditional love for Erikson. The difference is that before I came to the books with expectations to match, after having read the novellas I’m now ready to put aside what “I’d like and expect to read” and just let Erikson bring me where he wants. I’ve learned to respect and admire his work and forget the pettish critical eye of the always skeptic.

Third book in the series. I started reading it with very high expectations. I knew from forums’ discussions and reviews that this third book was considered the highest peak in the whole series. I came from the previous two that I loved and, especially, after being AWED by the three novellas of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach. Those that won me over and got my unconditional love for Erikson. The difference is that before I came to the books with expectations to match, after having read the novellas I’m now ready to put aside what “I’d like and expect to read” and just let Erikson bring me where he wants. I’ve learned to respect and admire his work and forget the pettish critical eye of the always skeptic.

When I turned the last page I had three thoughts going around in my mind. The first is a sense of emptiness that isn’t new to me when I finish a book that I’ve been reading for a long time. This book has accompanied me for the better part of four months, reading slowly but regularly as is my habit. When I close the book I have this feeling of emptiness, of characters that I’ve learned to know that remain in my head like echoes, lingering feelings. Like trails whose source I’m starting to forget. I know well this feeling and I know its name: it’s nostalgia. For me it starts as soon as I turn the last page. This time there is so much to remember that the feeling was amplified and leading into another: there is nothing left to read. I mean, there’s so much in this book that it leaves you feeling like you’ve read everything. There’s nothing else that could be written. Like a big “the end”. It’s over. The book embraced everything. Like Iktovian, Erikson seems to say, “I am done”.

This is epic fantasy. The embodiment of the abstraction. This book is like a shell, through which you can hear the sea. That’s the magic. It leads to something unexpected and shows you things vividly. Those last 150 pages are so filled with emotions, so inspired that they feel intimidating now. It’s only after those 150 pages that you understand where Erikson was going, you see the ultimate end. Three books to get there.

But I also have to say that I made this happen. While I read daily 15-20 pages for those four months, for the last 170 pages I sat comfortably on my couch and read without interruption from 1AM to past 5. In complete silence. This is something I consider like an obligation. Reading a book is a one-time event. Unrepeatable. It’s a gift that I don’t want wasted and so tried to get in the best way possible.

That feeling of emptiness, absolute fulfillment and nostalgia was the dominant one. Then I thought that it was unbelievable. Imagining in retrospective, the author that is about to write the first page, and is thinking about the last. You look back now that it’s over, and it’s simply impossible. This is not a human endeavor, it’s just crazy. Insane. It’s unbelievable the goals he set, it’s unbelievable how he wrote page after page, it’s unbelievable where he arrived. A mix of genius, insanity and carelessness. And, obviously, awe on my side.

Third on the stream of thoughts, was my surprise about a particular aspect. Throughout the book I saw one of his goals and believed it impossible. On the forums I even explained and discussed this point. Often Erikson deals with feelings and concepts that transcend the human level. In order to make a reader “feel” you have to use something that “resonates”. Something that we have in common. Something archetypal that we all know and share, and that we could impersonate again. That’s the only way you reach an emotional level in every form of art. If you read the forums the common complaint about Erikson is that his characters fail to really reach the heart, so it’s easier to appreciate the books through the mind than through the heart. Even his writing style is more rationally involving than is emotionally. In this particular case I’m talking about within the book, Erikson tries to convey a feeling of endless despair that belongs to the T’lan Imass (an undead race in the book). So I was explaining on the forums that I can appreciate Erikson’s goals, I can enjoy what he wants to do and be awed, but this will only work on the rational level since I’m just unable to “connect” with an alien race like the T’lan Imass. At various points in the book Erikson tries to “force” the feeling, and instead I felt like it wasn’t quite working. It was a best effort, but it just wasn’t possible and so felt somewhat “blunt” and failing in the end. Well, the end of the book was able to achieve fully what I felt as impossible. Throughout the whole book it seemed that Erikson was rinsing and repeating, forcing something that wasn’t working well. With the end of the book he succeeds. Those feelings passed through without losing completely those alien traits. The book made me live something that was utmost unique. That single aspect.

That’s why I think the book is the embodiment of epic. It’s insanely ambitious, sets goals impossible to reach, staggering. And gets there. “I am done”. And it’s because he is done that I wonder where he found the energies to write further. There isn’t anything else to write. It’s over. This book reads as the final chapter. The hanging threads are superfluous sophistications that may as well stay there floating in potential. I read book 1, intrigued, though the ending was rushed and too forced in its spectacularity. I had my mind filled with questions that I wanted answered (as after watching an episode of Lost). I started reading book 2 to get my answers. Loved Heboric because as an historian he was the symbol of all my longings. By half of this second book I got most of my answers. By the end of the book all those answers were turned on their head and all my theories fell apart. In fact I was upset because I didn’t think the plot was going to make sense. Too many contradictions. Besides, the last 250 pages weren’t written as well as the rest of the book. The usual convergence felt again a bit too rushed and two of the three plot lines were dull in the way they were presented (as usual I explained this better in the comments to the book). Great book nonetheless, but I was still there longing for answers and to start making sense of the whole thing. Then I read the novellas that suprised me for all different reasons. No more caring much for the intricacies of the plot, but being awed by the *writing* itself, the sheer creativity and surprises at every page. A careful masterpiece, word by word, in a completely different way from the other broader books. I started this third book to get back to the hanging plots left by book 1, once again to get my answers. By half of it I got most of my answers, by the end of it, I didn’t care anymore.

While reading through book 1, 2 and most of the third I was wondering why there weren’t more discussions on the forums about the mysteries and hidden plots. The great majority of readers are much further with the books so I believed that they OUGHT to know more about what I wanted to know. Instead not only they didn’t, but in many cases they didn’t have any clue about *what I was asking*. Like if I was reading an entirely different thing. Well, it was true. There are two aspects to consider. One is that this series is like a parallel to Lost, the TV series. Both use some of the same tricks and Erikson uses some of them even better. One of the tricks is to force the attention of the reader onto something else. You fill a first part with mysteries, then continue to shift the focus till the reader/spectator is enthralled by brand new mysteries and forgets about the firsts. Erikson does some of this through some kind of chinese boxes, and it works great. What you think was a mystery onto itself, reveals to be part of a MUCH bigger tapestry. The box contained in a much bigger box, and the bigger box into another. Those questions and mysteries kind of fall to irrelevance when you realize that all you got was nothing in the bigger picture and you were trying to put together a puzzle of 5000 pieces by matching together just an handful. If you look for Agatha Christie kind of flawless weaving you are going to be disappointed as it is very likely that some of the pieces are mistakes and not just masterful misdirection (and multiple level of meaning, something Erikson does well), but the way he manages these unexpected transitions from a lower level to an emergent one is eminently enjoyable. It’s also with this third book that something changes. In book 1 and 2 you were just trusting the writer and just add more pieces to a borderless puzzle. It was pure chaos as there was nothing conventional or expected. A blank board with a stream of pieces coming in, the reason why most readers are welcomed with absolute confusion and bafflement. The third book instead starts to fill the gaps. After having drawn the horizon, you start to grasp the big picture and “belong” more to the world Erikson created. So starting to understand the pieces, recognize them and play with them. I was saying how the mysteries “escalate” to upper levels so broad that the details fade out, and how Erikson diverts the attention to new “live” threads, making others less important. Secondly, and here we come to the point, it succeeds where he was failing. Characters, emotions. After working so much on the rational level he finally succeeds to bring the characters to the front, and with the ending of this third book all of the sophistications of the plots that crowded my thoughts during the previous books became suddenly less relevant. I wasn’t thinking anymore about why Dujek was contradicting Laseen, or who killed who during the sieges of Pale. I was thinking instead of the characters and the sense of emptiness (nostalgia) they left in me. I was there sharing something with them.

After this endless stream of unbelievable praises do I think the book is flawless? Well, if I have to rate it, it would score a perfect. Simply because it is a success on what it wants to be, and what it wants to be is something I’ll remember for a long time. It doesn’t mean that the book is perfect, but that the problems fade out and I don’t consider them as relevant as in the previous books. For most of this third book I thought that the writing quality and style was overall a little below of book 2 (or at least book 2 minus two plots at the end of the book as I explained in that commentary), I also thought that if I had to rank them I’d put the second on top. That before reaching the end of the third book. Now I really couldn’t put this third book below and I understand all those readers who think that it’s the highest peak of the series. Deadhouse Gates has an overall better execution, beautifully written, but the ambition (and payoff) behind it just can’t compare with what Erikson does here.

There are other aspects I can criticize. The book is, shortly put, wasteful. To those who think that books this long (1100 pages) are unnecessary, I’ll say that these are not 1100 pages written by a writer who’s trying to fill 1100 pages. These are 1100 pages written by someone who’s trying to *squeeze* into them all he has in his mind. The pacing of the book is relentless and those pages without action are the pages that in the end are more important and filled with revelations (so moving the plot). I say this is wasteful because there’s just too much. While the end works on its own and justifies the journey, for the first half of the book Erikson wastes a number of valid ideas without playing them to their full potential. He fires them into the air clumsily and brings them down shortly after. He wastes opportunities. He builds up mysteries only to spoil them two pages later (if not on the same page). The pacing is so sustained that you have no time to let characters and feeling linger enough. A case of excessive creativity and drive. In retrospective I now understand better where this “urge” came from. There was to much to do for the destination that he already had an insane number of balls to juggle in the air. As I said, this book is insane.

At some point halfway through the book there’s an idea extremely interesting. One of the main characters has a crisis of faith and starts to question what he believes in. His words are pure beauty and deep. This is also an extremely important transition in the plot. I’ll quote it again:

And perhaps that is the final, most devastating truth. The gods care nothing for ascetic impositions on moral behaviour. Care nothing for rules of conduct, for the twisted morals of temple priests and monks. Perhaps indeed they laugh at the chains we wrap around ourselves – our endless, insatiable need to find flaws within the demands of life. Or perhaps they do not laugh, but rage at us. Perhaps our denial of life’s celebration is our greatest insult to those whom we worship and serve.

The character here has made a vow to his god and is now wondering if the gods are really caring about these demonstration of faith. Maybe that vow is instead an insult to the gods, what he calls a “denial of life’s celebration”. Why life shouldn’t be experienced fully? Why “our endless, insatiable need to find flaws within the demands of life”? It’s beautiful not just because of how it was written, but because those words have depth, truth (and not, like Gene Wolfe, just a way to “adorn” in fancy, sophisticate words a simple concept).

‘You question your vows.’

‘I do, sir. I admit to doubting their veracity.’

‘Has it been your belief, Shield Anvil, that your rules of conduct has existed to appease Fener?’

Iktovian frowned as he leaned on the merlon and stared out at the smoke-wreathed enemy camps. ‘Well, yes-‘

‘Then you have lived under a misapprehension, sir.’

I won’t spoil the solution of this passage, but I’ll use it as a concrete example of how Erikson doesn’t play many of his ideas to their full potential. This whole transition and character development (and resolution) I’ve hinted here is contained in TWO PAGES. It is beautiful, deep, not at all simple. Filled with potential and interest to my eyes. Kept me glued to the book. But completely contained in 2 pages among 1100. This is the pacing of this book. All the book is like that, filled with different threads and crazy ideas that come and go page after page. Every page is a pivotal point and this rhythm so sustained becomes somewhat detrimental as there’s no way to make all these things “settle” in the mind of the reader. Once again, familiarize.

This is what lead me to write that other commentary about character development. Without “slices of life” or time to familiarize, the readers will feel disconnected from the characters in the book. If deep transitions and shift of motivations happen in the space of two pages, like the Iktovian example here, then it will be hard for the reader to relate to them and share/understand their feelings. At the same time this is a strength for Erikson. His unique style. The journey isn’t a typical, already seen one, the characters aren’t conventional, and they develop in unpredictable ways that demand a big effort to the reader in order to keep the pace and understand this type of complexity. Lacking the redundancy that is typical of the genre (these days I’m reading Goodkind and the parts of it that work well work exactly because of the redundancy). The more I think about the book now that I read it from beginning to end, the more I realize that there wasn’t any other way to write it.

Typical deus ex machina associated with Erikson are part of this case. There are many in this book. They make sense, are part of the world. But the tapestry is so broad and the threads so disparate that when it all comes together in the end you can’t avoid the feeling that all of that was “guided”. This will annoy purists, but in this case the “intent” is itself the reward. There wasn’t any other way. This story told itself. The hand “driving” plot threads and characters along isn’t an intrusion, but just the way the story told itself in the way it should. Iktovian is an example because Erikson builds the character through the book to “get there”. There wasn’t any other way to do it. “Destiny” as a destination that ultimately follows a sequence of steps. Similar to the Greek myths and legends that Erikson uses as inspiration, and whose metaphoric value he tries to give life to. Salvation, tragedy and a whole lot of other undertones. Themes high and low mixed together. Sleight of hand and awe.

Either you follow (and be willingly to follow) Erikson or this whole thing just won’t work. On the forums I read all sort of criticism and a good amount of it is poorly motivated. This leads, even from myself, to claim that those readers “do not get it”. Too often what happens toward the whole genre, and is promptly defended by everyone, happens again within. People attack the book because it has an excessive use of magic, powerful characters, huge battles. Well, my opinion is that these books are great IN SPITE of those. It is when Erikson is most realist and delves deep in his themes that he is most successful. But why using the spectacularity as an argument to diminish the books? It’s “serious literature” vs fantasy all over again. The same mistakes repeated by those who are this side of the fence (appreciating the genre) and that should know better than criticize something through stupid, superficial arguments. It’s diminishing without understanding. So I say that when those arguments are used, readers “do not get it”. Erikson is a lot more than what drifts on the surface. If all you notice is the powerful magic and characters then it means you are gliding on. Losing the great majority of the meaning of those words.

The payoff is then only proportional to the dedication. Erikson will never work too well for the large public. It will never be an easy and almost safe recommendation (like Abercrombie or Scott Lynch). It will never be for a “majority”. It will never work for a variegated public on different levels (and ages). But if you are on the same line and are interested in its themes and intent, then it will be nothing short of grandiose. More than a book, a journey.