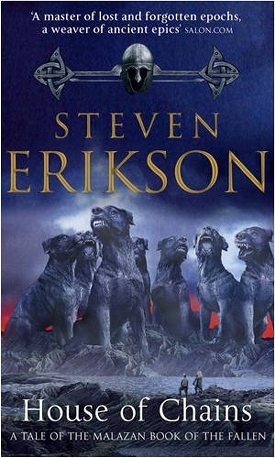

House of Chains is the fourth in the 10-books Malazan series. These days, these hours, Erikson is intensely busy writing the last chapters of the last book and bring to a close a journey of staggering ambition. Reading this fourth felt like standing on the shoulder of a very tall (jade-colored) giant. As with similar(?) long series it’s interesting to see the power-game, the ebb and flow of the single book compared to the others. When I was at page 700 or so (on a total of 1000) it dawned on me that this would become, with certainty, my favorite. 100 pages from the end the story proceeded resolute with a sense of finality and inevitability. Like the dramatic ending a movie whose sound is deafened, muted, so that the intensity of what you see comes out unadulterated and with all its power. But it is immediately past this apex, in the very slight and calmer descent that follows, the remaining 30-40 pages, that the more meaningful and stronger revelations are delivered, and the characters reached down for my soul. The book had already gauged his way as my true favorite and was set for a foreshadowed ending. I only expected closure and rest, yet the book still had PLENTY to deliver, and surprise me, and offer emotions to share.

House of Chains is the fourth in the 10-books Malazan series. These days, these hours, Erikson is intensely busy writing the last chapters of the last book and bring to a close a journey of staggering ambition. Reading this fourth felt like standing on the shoulder of a very tall (jade-colored) giant. As with similar(?) long series it’s interesting to see the power-game, the ebb and flow of the single book compared to the others. When I was at page 700 or so (on a total of 1000) it dawned on me that this would become, with certainty, my favorite. 100 pages from the end the story proceeded resolute with a sense of finality and inevitability. Like the dramatic ending a movie whose sound is deafened, muted, so that the intensity of what you see comes out unadulterated and with all its power. But it is immediately past this apex, in the very slight and calmer descent that follows, the remaining 30-40 pages, that the more meaningful and stronger revelations are delivered, and the characters reached down for my soul. The book had already gauged his way as my true favorite and was set for a foreshadowed ending. I only expected closure and rest, yet the book still had PLENTY to deliver, and surprise me, and offer emotions to share.

These weeks I spent reading House of Chains were also the weeks of Lost ending season (the TV series), which lead me to draw certain parallels, both thematic and about the plot. Similarities are evident even on the superficial level, and on the forums I was explaining that I was watching Lost for some of the reasons I was reading this series of books. The staggering ambition, the exponential layering, the subversion and reversals in the plot, the continuous challenge to perceptions. The difference, as I already discussed, is that Lost always left me (and many others) unsatisfied. Even the very end left the plot unresolved. With the Malazan series instead it’s a whole different deal. Reading this book, at various points, I thought that if it was to end right there, in the middle of the narrative, it would still feel completely satisfying and accomplished. Erikson as an author is far more generous and I feel that what he does is always honest. I never once felt cheated. Which also leads to the broad theme of “truthfulness”, that Erikson fulfills for me. Reading this series is not an easy task for anyone, but I know that it largely rewarded my effort. It delivers all it promises, then more, far beyond expectations that continue to rise as the story goes and branches out to embrace what you don’t think can be embraced. I am humbled because I know that this is one rare effort that won’t likely be matched anytime soon, if ever. I’m glad that I find it so close to things that matter for me, at the core, and that I seek in a book. It completes what I think and I follow devotedly because it already proved aplenty that this journey is worth all the dedication I can give to it. This to say: Erikson, especially in this book, doesn’t lull and drag you along with vane promises. He delivers, page after page. The physical shape of the book, right there, weighting far more than you think. Worlds that the written word can open, and worlds that, deep down, feed on something true.

This, for me, has nothing to do with the notion of escapism. At least if you don’t consider escapism the illusion of the discovery of something meaningful, that matters. And so the thematic aspects. I guess that this couldn’t be more misleading. “Themes” make me think of very boring books that have nowhere to go and preach on banalities or feast on rhetoric. Or the celebration of some sort of morale. I have a natural tendency to oppose and refuse these things because I always find them trite or partial. Erikson instead makes these aspects very real and makes surface their contradictions. The narrative is driven by purpose, a lucid intent, that doesn’t lead recursively to itself, going nowhere. Turning a wheel that turns and turns but goes nowhere. Those themes, taken as abstraction, are always brought back to the ground. They don’t wander on a detached level, different from the plot. They are intricately woven and matter on a concrete one. The biggest revelations can please a reader just for what they are, the fun of following an engaging story filled with unexpected twists. The last 70 pages of this book are a frenzy of plot threads that get tied and resolved one after the other. And each, if not to be carried away by this surging tide, turning the pages, would make you look back with unprecedented clarity. The thematic aspects here bind the narrative.

‘The stigma of meaning ever comes later, like a brushing away of dust to reveal shapes in stone.’

The structure of this book is slightly different from the preceding ones. It starts with about 250 pages from a single point of view instead of jumping all over the place. I think this choice is perfectly placed. It’s not easy to have the story move again after the ending of ‘Memories of Ice’. Starting from a blank point, apparently unrelated, offers the narrative the possibility to gain momentum. Especially because all we learned through three books here becomes the cipher of what is going on behind the curtain of deception. An higher level of awareness that you have, as a reader, above the level of the narrow point of view. An second-level of observation that reveals a bigger truth, as you are yourself, as reader, deceived in turn, when you thought your position let you see clearly where the deception actually was. A clever trick indeed. But again, done to understand the story on a deeper level, and bring the reader right into it, with an active role. Not so many books do this. You may think this is some ‘mental’ stuff I imagined, but no. This is why I said the book is generous. It has not the esotericism and bloated pretentiousness of Pynchon, this book BEGS you to understand it. It doesn’t hide for the simple pleasure of obfuscation, nor it lulls lathering in redundancy.

‘In any case, to speak plainly is a true talent; to bury beneath obfuscation is a poet’s calling these days.’

Now this review is coming out rather abstract and vague, yet I’ve pages of notes about specific aspects but I don’t think I can go anywhere with them. This book offers a myriad of suggestions that you can taste and elaborate any way you want. Take for example the book of Dryjhna. It’s a story that starts in book 2. This is Erikson doing his typical play on some established fantasy conventions (and in book 2 he resolves it delivering a spectacular surprise). In this case the ‘book of prophecies’. We’ve had these plot devices dealt in every possible way in the fantasy genre. Here the running joke is that prophecies are left vague because through this very quality they can be pragmatically adapted to the changes of time. A way to keep them relevant and useful for those who actually wield that power for their own secular purposes. In the end prophecies are nothing more than excuses to exploit a population. But it’s the real revelation of the truth (or better, the deceit) behind the book that makes it ultimately worth saving. The book is revealed as a fraud, but this revelation makes the book valuable for what it actually is, which consequently infuses it of the power it lost. A full circle, but, as it closes, the power of the book goes from misplaced and false, to something true and valid. It got somewhat cleansed in the process. This I’ve just explained is a very minor plot thread, almost invisible. Maybe two pages in total name it, yet, by ways of Erikson, what this book (of prophecies) represents echoes with everything else that goes on the major level. Everything intricately woven together at different levels.

There are certain plot threads, on a second inspection, after the tide of the last 100 pages passed, that seem somewhat spurious. Though this is typical of Erikson as the plot branches out to previous and following books. They are the most obvious links. But the reason why they are there is because they are part of larger loops. They are meaningful in the single book, have an impact and purpose, but the story arc isn’t brought to conclusion right there. When I finished book 3, I thought that Erikson was at his maximum possible reach. Controlling so many characters and plot threads while delivering a so huge conclusion was absolutely spectacular. House of Chains is on a somewhat smaller scale and more personal. It continues directly from book 2 and draws from the qualities found there. Yet, this smaller scale was only apparent and Erikson shows here a stronger control of plot. He still improves. Book 3 had from my point of view a more uneven quality compared to the 2nd, even if as a whole it came out far above just because of its impact and staggering ambition. House of Chains shows a tight control and a clear intent. It is lucid in a way no previous book was. More effective and straight to the point. Every aspect I can consider is overall improved. The prose itself stays terse as is typical of Erikson, and gains efficacy. No wasted words, no lingering, yet also not as wasteful as it happened in Memories of Ice. On some of my notes I wrote how in books 1-3 we saw an expansion of the plot. An exponential multiplications of different factions and factions within factions. House of Chains instead represents a kind of contraption that doesn’t reduce the reach of ambition of the plot, but that actually leads to an absorption of the various branches into an unitarian mythology. The nature and truth of many things is revealed, and this revelation draws everything together. It all makes sense and even sheds more light on previous books in a way that makes them shine even more. Following books improve the previous in retrospective, add significance. Especially in this case for book 2, that was already excellent. House of Chains is an open celebration of Deadhouse Gates, yet this doesn’t put it in its shadow in any way. They just contribute to each other.

Want one flaw? Named characters lead the story. Yes, there are A LOT of them in that “named” list, but the terse style of Erikson lacks some naturalness if you care for it in a book. I’ve pointed this out in the past. There are no slices of life scenes here. No getting used to the characters or lingering with them for the mundane. This story has momentum and moves on. We don’t get to see what isn’t strictly relevant. Yet, this also means that these plots are sometimes too neatly wrapped up. Too coincidental and convenient. Everything pivots exactly where it should, and no matter how HUGE is the landmass itself, characters that travel seem to ineluctably constantly bump into each other. Sometimes it feels as if the “real world” is missing. As if the plot was eradicated from its natural place and made an example of. I doubt you could tell such story in a different way, though.

I loved this book. Not just because it has an excellent execution, but because I loved it also on a more personal level. The biggest mystery is how Erikson is able to gather the strength and will to start again from a blank page after such a huge showdown. I’m merely a reader, yet this was exhausting in a positive way. So much was brought to a satisfying closure. No idea where this will bring me next, but I have trust in the writer that it will be more than worth it.

The last few lines of the epilogue, in italics, are probably the biggest and more powerful revelation ever. Sustaining the whole series. (hopefully enough to keep Erikson himself afloat)