“Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.

“Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.

The content and purpose of the book fit as a retrospective: from one side we get to see what happened in the particular night Surly/Laseen claimed the throne of the Malazan empire while declaring the death of the previous ruler, Kellanved, who had been missing for quite some time giving Surly the opportunity to solidify her position. From the other, through flashbacks, we get a close-up of “The Sword”, the six bodyguards/champions around Dassem Ultor, champion of the Malazan empire, and particularly Dassem’s betrayal that was vaguely commented between Paran and Wiskeyjack in that GotM prologue.

Here comparisons between writers are impossible to avoid since we have two of them writing the same material and aiming for complementarity. So the big question is if Esslemont can match Erikson or at least stay relevant and add something worthwhile, with expectations being very high and not playing in Esslemont’s favor since it’s complicate to debut when the main series is already established and halfway through. That was also my main concern: trying to weigh Esslemont potential not just for this book, but also for the upcoming contributions. The first 50 pages were quite revelatory for me. Esslemont is a rather competent writer, the beginning of the book is well handled, solid prose, written and paced perfectly. There wasn’t anything suggesting it was a debut instead of the work of an established writer. I also thought the style was distinctive and not clashing or conforming to Erikson. Especially, I think Esslemont did a wonderful work on Malaz itself, the city. The place comes to life, the shadowy atmosphere rendered perfectly with its narrow, twisted alleys, the very quiet and suspicious people on the brink of insanity. From Mock’s Hold perched on the cliff (and the inevitable wink to Mock’s Vane), down to the sprawling ramshackle houses. It gives a sense of real place and I still now consider this the biggest quality of the novel. The town being the true real protagonist, interpreting perfectly the understatement of the conflict it gets tangled in. The true heart of the empire, yet far from the celebration of triumph or glory of a capital. It’s a haunted town everyone would get away from, sullying and miserable. So weak and vulnerable, yet caught in the eye of the storm and holding desperately. Reminds me of a place that would fit perfectly in a Lovecraft story, madness stalking behind every corner.

Speaking of tones and atmosphere, I think that, more than Erikson, Esslemont draws plenty and openly from Glen Cook. The whole novel echoes with the first chapter of The Black Company and even more with the whole second book, “Shadows Linger”. Lots of elements in common, the first chapter of The Black Company was similar to an horror story, with the company caught in an unusual situation and slowly drifting toward dread, discovering corpses everywhere while the town they were stuck in descended into chaos, the Hounds of Shadow in “Night of Knives” filling perfectly the role of the “forvalaka”. Same for “Shadows Linger”, also set in a gloomy small town, inside filthy inns and nearby mysterious places. Townsfolk involved in ominous practices that slowly escalate to a disaster. Inspiration here is not a flaw, since Esslemont uses all this competently and functional to the story he writes, without giving the impression of a diminished copy.

There are problems, though. Everything is set perfectly in those initial pages, but as the story progresses it also loses its strength. Instead of escalating it kind of folds without delivering its potential. From my point of view the problem is that Esslemont fails to switch gear when needed. There’s a moment in the story when the spooky “fairy tales” and legends descend, truly, on the real world. Kiska fits well as a POV there, because we have a naive perspective on a situation that is quickly transforming. But when hell breaks loose the story is stuck in the preceding naive tone and the dramatic intensity is underachieved or lost. Esslemont stays too much on one fantastic, dreamy level that is excused when the story is still in the build-up phase and what is to come has to feel distant, the menace being remote. But when it closes it lacks realism and the characters are still lulled by the writer, never at risk, never exposed outside their own cliche. They stay put, characters as devices, their perimeter containing them, and them carefully stepping to never dare becoming real characters. This is the kind of babysitting that never lets the story run wild and deliver. Somewhat like a cheat.

Kiska fails to become a real character, ideally she should be hammered out of her fancy fantasies (echoing Paran’s own “I want to be a soldier. A hero.”) and crushing on reality. She starts wishing to be the heroine, admirably skilled in her dreamy land, but she stays there even after. She glides over everything, undamaged, in truth, beside a few minor bruises. The kid outskills everyone else, she lives her dream in reality WITHOUT EVEN PERCEIVING THE TRANSITION. She enters and exits the novel with the exact same mindset, nothing learned. She’s lulled in her dream as the world comes to coincide with it, instead of her coming to grips with reality. She starts naive, and ends up with all her dreams fulfilled without even once confronting reality. Her role, as cliche, fits perfectly, if only at some point the cliche would be used to spring her (and the escalation of the plot toward dramatic intensity) to a whole new level. Instead the whole structure folds. We have these two levels. The low-ground perception of townsfolk, with all their superstitions, and then the crushing of the convergence, the Shadow Realm that descends on the city itself, becoming very real and tangible. The townsfolk barred in their own houses, praying the dream to end soon, the storm outside. Yet, on the level of the novel, it’s the “reality” that is lifted up to “fairy” level, with magic becoming magic, old wizened and long-bearded guys becoming wise wizards, the heroine being tested through riddles. Lots of blood, corpses everywhere, but it’s just tomato juice on redshirts, come the morning the bad guys are dead, the roads relatively filthy as usual, some fallen bricks and crumpled walls, heroes survived heroically, the heroine got her alluring, mysterious boyfriend. When do I wake up?

Erikson’s work on the series can be summarized as: “Nothing is as it seems”. Here it’s the opposite: everything is as it seems. No subtlety, no tricks on perceptions, no layers. Leading to another consideration. Esslemont’s characterization is actually well done, at least in presenting the characters if not in their development. His overall style of prose, narration and characterization is traditional compared to Erikson, but “traditional” doesn’t mean “bad”. The introspection here is “full-on” and helps leading the narrative. You get into the characters’ thoughts in a way that you never find in Erikson. This meaning that this book can be more readable and accessible, even enjoyable. Erikson’s style, being infinitely layered, prompts you to put down the book and think about implications, Esslemont is more like the page-turner, pushing the story onward, curiosity taking the lead and the reader more involved in the destiny of characters. A more emotive/empathic approach of a character-driven story. The book can be read quickly and is quite fun but it stays on that level.

Thinking of “purpose”, the story is aimed to shed some light on a crucial point of the history of the empire. The book is filled with juicy details that can please the fans of the series. Lots of “fanservice”, which is a good thing. Yet, this is not a necessary read, nor a recommended one. Concretely, it adds nothing worthwhile. It uses and consumes without creating. We see lots of details about what went on, but they all seem disposable and none really clarifying. The real deep motives stay deep and unrevealed, deliberately untouched in this book. The betrayal of Dassem Ultor is a pivot of the novel, yet absolutely nothing is added to what we knew. We see it happen, but what we see explains nothing about what happened. Another instance of “everything is as it seems”, or there’s nothing more than what meets the eyes. Another big flaw being that the more is revealed, the weaker the story. Instead of enhancing and realizing complexity, it kills it. No surprises, no revelations that open new interpretations and scenarios. The few answers that come only close some dead-ends of the overall plot without producing anything. Lots of potential when it comes to Laseen, but the character is flat and hiding absolutely nothing. She’s merely there and passive, with the lack of active presence hiding absolutely nothing: she’s really doing nothing if not what is plain. Mystery that hides nothing. Same for the confrontation between Claws and Talons, reduced to a confused ninja battle between caped figures. Shadowy capes hiding nothing. Conspirators whose conspiracy is held on plain sight.

From this perspective the book is immature. Not again in the competency of Esslemont as a writer, but in failing to cross that line between adolescence and maturity and everything it represents. The falling of myths and naive dreams, the facing of failure or helplessness. The same done by some “fantasy” (as genre) trying to come out of its stereotype as “young-adult” escapist entertainment, whether it is George Martin or Erikson or whoever else, trying to open up the genre to a more mature type of narration, more complex, layered and unbound from strict conventions and types. “Maturity” or even modernity: no more absolutes, but points of view, layers, perspectives. This book fails to cross that border. The characters are caged into themselves, being plainly what they seem to be and within their narrow stereotype or functional role in the plot. In various occasions the story directly reminds of “young-adult” tropes (here straight from “Neverending Story”):

If she did succeed in returning, Kiska vowed she would head straight to Agayla’s. If anyone knew what was going on – and what to do – it would be her. Never mind all this insane mumbling of the Return, the Deadhouse, and Shadow. What a tale she had for her aunt!

And ending with:

‘Yes, I will. Thank you, Auntie. Thank you for everything.’

Agayla took her in her arms and hugged her, kissed her brow. ‘Send word soon or I swear I will send you a curse.’

‘I will.’

‘Good. Now run. Don’t keep Artan waiting.’

“Don’t keep your boyfriend waiting”. It’s then hard to lift the plot to dramatic intensity when this distance of perception never closes. Brutal fights are witnessed, but so alien and detached (or described through morbid badassness) that they never come real. Threat never getting close if not in a fake way. Kiska never falters, no matter how unbelievable is that behavior even for a prodigious child. Every impossible action or behavior excused by mere exceptionality. Temper, the other POV, is not different. Even here the character is initially very solid and well presented. A paranoid veteran hiding from his past. But all plot points are fortuitous and convenient, and even the flashbacks recount battles between invulnerable champions with a lot of useless redshirts around them. Halfway through the character moves from a well realized one, to click into his functional stereotype. When he exits the story he’s the hero who saved the day whose deeds remain unknown. Close your eyes and shadows become monsters crawling out from under the bed. You wake up, it was a dream. Esslemont fails to play properly with this and switch tone. Everything stays up there, suspended into adolescent mythology. The mythical story described exactly as the cleaned-up myth wants. Nothing being ever threatened or compromised.

The series is not powerful for its mythology and form, but because Erikson, as a writer, instilled meaningfulness into it. Made it relevant for what it has to say and the way it challenges perceptions. But Esslemont doesn’t seem to add something of his own. He delivers the story without delivering a purpose. If Erikson writes to reach far outside mere “escapism”, Esslemont stays strongly rooted into it. The story sits on the surface level, which I guess explains why the fans of Esslemont himself are often those who judge Erikson’s book as overlong and slow. Erikson digs deep on the level of meaning, is concerned about the reason to say something, is tormented for reaching out to the reader and shake him. Esslemont fails to have a drive in this novel. There’s no “necessity” of the narrative intent. Outside the entertainment value, being said or unsaid is the same. Why reading this book? Because it’s still a good read and if you are a Malazan fan you’d want to know more and enjoy the story, but I thought that the mysteries revealed would stay better mysterious and ambiguous. Instead of being revealed so plain. It’s a fun and well executed roller coaster if you enjoy Malazan mythology, but it’s still a roller coaster.

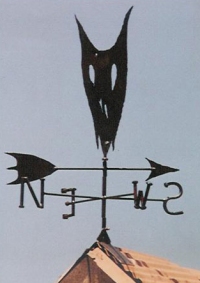

“Mock’s Vane” is the object whose description opens the Prologue of Gardens of the Moon. I was briefly discussing its description on Westeros forums when I noticed that on Tor reread it was interpreted in a completely different way, without triggering any debate. So I thought it was worth elaborating here.

“Mock’s Vane” is the object whose description opens the Prologue of Gardens of the Moon. I was briefly discussing its description on Westeros forums when I noticed that on Tor reread it was interpreted in a completely different way, without triggering any debate. So I thought it was worth elaborating here. It makes sense but I think my interpretation is more accurate and convincing. I’m not a particularly intuitive guy and these things usually defy me, but in this case I used a rather simple framework. I took the object and divided its basic qualities. Those traits will probably qualify what the vane stands for/symbolizes.

It makes sense but I think my interpretation is more accurate and convincing. I’m not a particularly intuitive guy and these things usually defy me, but in this case I used a rather simple framework. I took the object and divided its basic qualities. Those traits will probably qualify what the vane stands for/symbolizes.

“Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.

“Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.